Head north out of Fredericksburg on U.S. 87, and just about the time you reckon you’re lost, you’ll find the Hill Top Café waiting to greet you.

Head north out of Fredericksburg on U.S. 87, and just about the time you reckon you’re lost, you’ll find the Hill Top Café waiting to greet you.

The establishment’s name writ large in cerulean blue on the roof matches the white building’s trim that, along with the hot pink crape myrtles and resilient sunflowers, provides a splash of color to the sun-baked browns and withering greens of the water-deprived Hill Country.

Pumps outside the restaurant housed in an old gas station sit dormant, their only job now to provide shade for the small olive trees for sale near the entry of the joint that looks as if it’s been relocated from a movie set.

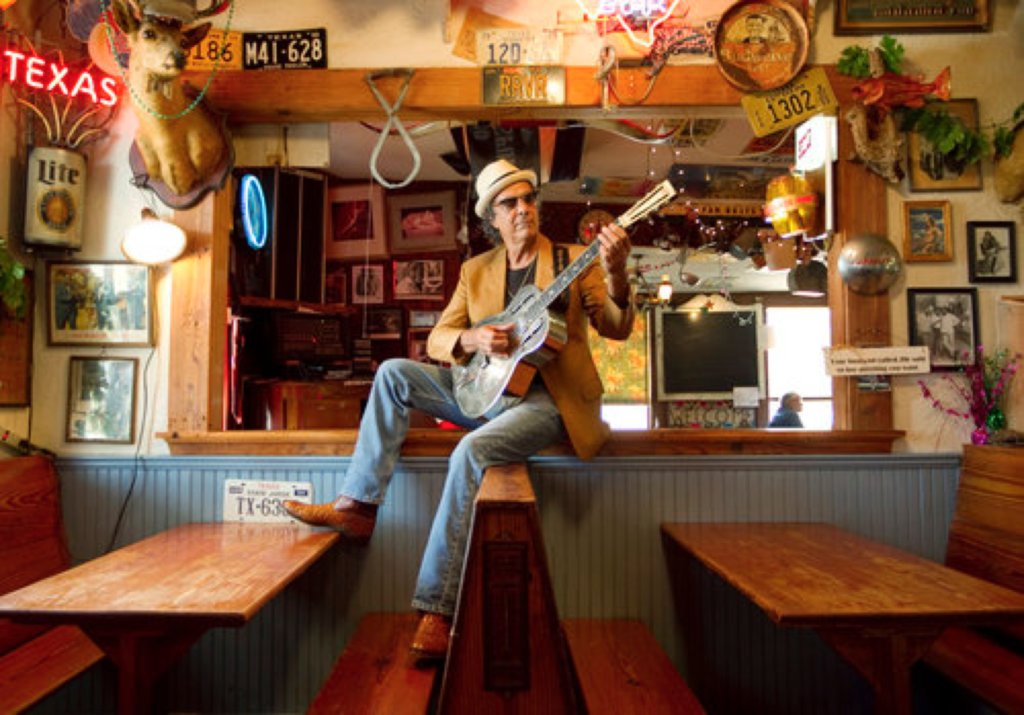

Classic gig posters and vintage album covers paper the walls inside: Records from Slim Harpo and Lightnin’ Hopkins share space with weathered art promoting a Professor Longhair show at Tipitina’s in New Orleans. Pictures that contain stories you’d kill to hear are mixed among the cultural artifacts. In one, Eric Clapton shares a beer; in another, Jimmie Vaughan’s face tilts with a grin.

The common denominator in these photos is a younger version of the affable and effortlessly hip man in Wayfarer sunglasses, brown blazer and ostrich boots who greets Hill Top Café customers while slipping in and out of Spanish with a member of his kitchen staff as Harry Choates sings “Valse de Lake Charles” on the stereo.

With his pencil-thin mustache and tendrils of salt-and-pepper hair, Johnny Nicholas, dressed in a black T-shirt with a gold cross draped across his neck, looks like Mickey Rourke probably wishes he did.

The emergence of the renowned blues guitarist signals that the Hill Top Café is no museum or sleepy monument to the blues. It serves as a vital extension of a man who has helped cultivate and honor the tradition the restaurant’s artifacts commemorate and celebrate.

After years of keeping a relatively low profile out in the Hill Country, sporadically traveling for gigs, Nicholas has put out his first studio album in six years. With “Future Blues,” Nicholas offers to the world his authentic blues sound that until recently had been largely reserved for the customers who were lucky enough to catch one of the impromptu sets at the Hill Top Café.

Nicholas and his wife, Brenda — the Hill Top’s true engine, as an unprompted Johnny Nicholas will let you know — opened the restaurant in 1981 after moving to the country from Austin. Mixed among the scenes of musical legends at work and play are pictures of Astros. Not the Houston variety, but the Little League teams sponsored by the cafe. That’s what brought the Nicholases out to this spot smack dab in the middle of nowhere: family. The chance to be closer to Brenda’s and the desire to build one of their own.

It might not be in vogue for young musicians to admit, but Johnny Nicholas, father to sons Willie, 18, and Alex, 23, is an unabashed family man. The restaurant echoes the experience of his own childhood growing up in his grandmother’s restaurant in Rhode Island. Family taught him the not-mutually-exclusive values of hard work and joyful play. And it was family that first turned him on to the other love of his life.

A young Nicholas often would accompany his family to Greek functions where he would hear rembetiko music. While the bluesy, folksy music seemed foreign to him, its soulfulness resonated with the child. But it was the radio and his older brother Billy’s record collection that first truly inspired Nicholas.

“The first people that I really listened to and grooved to when I was a kid were Ray Charles and Fats Domino and Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, all the stuff R&B-wise that was popular in that time,” Nicholas said.

His brother not only turned him onto Charles, he also helped a 10-year-old Nicholas transform an old cigar box into his first guitar.

While the jazz and folk festivals of Rhode Island offered a tangible taste of the musical world which he longed to inhabit, the insatiable Nicholas left home after high school to track down his heroes and learn from the greats.

His blues pilgrimage took him south in 1966 to New York City and clubs like Steve Paul’s Scene, Café au Go Go and Ungano’s, where a star-struck Nicholas first saw Howlin’ Wolf perform live. Not satisfied to simply attend gigs, Nicholas tracked down the legend at the Albert Hotel and, after receiving an introduction from guitar player Hubert Sumlin, spent the entire week hanging out with Wolf and his band.

“It was the deepest and most impressive thing I’d ever seen,” said Nicholas, who went to every Wolf show that week in New York City. “It had a really deep effect on me about the Wolf himself and what kind of person he was. On stage, he was as wild and amazing and as great a showman and as great an artist as I’d ever dreamed he would be from listening to his records, but then at the hotel hanging out with him \u2026 he was such a down-home guy. He was also a real business man. He had ledgers for all the guys, and he told me, ‘If you don’t take care of your business, it won’t take care of you.’ That made a big impression on me. He reminded me a lot of my family and the way my dad was. My folks, they loved to have fun, but they were also very strict in other respects.”

A hunger to learn and travel cut short Nicholas’ time at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa., and the young guitar player headed to the blues mecca of Chicago, where he cut his teeth playing at places like Pepper’s Lounge and earned the respect of those he had long admired.